Many people “know” that that the Buddha “was born a Hindu.” But this, like the ideas that he was a prince and that he left home after seeing “the four sights” is also untrue.

The “Hindu Prince”

Writers often bundle myth of the Buddha having been born a Hindu together with his supposed princely status. For example, a website called “Smart History” says:

The man who became known as the Buddha was a Hindu prince, named Siddhartha Gautama, who was born in the 5th or 6th century B.C.E. to a royal family—the leaders of the Shakya clan—living in what is now Nepal.

This is just one of many places making this claim. The problem is, as I’ve said in earlier mythbusting articles, that many writers just repeat what other writers have said. They don’t check this information against the scriptures, which are our earliest and most reliable guide to the Buddha’s history. And so myths can go unchallenged for centuries.

This presentation of the Buddha as a former Hindu is just a terrible, horrible, no-good, very bad account of history.

Brahmanism versus Hinduism

Practitioners of the spiritual traditions around at the time of the Buddha didn’t necessarily give names to their religions. There was nothing called “Buddhism.” Followers of the Buddha just said they were “followers of the Buddha” or or his Dharma. They didn’t say they were “Buddhists.”

Brahmins don’t seem to have had a name for their tradition either. Buddhist say they were Brahmins who had “mastered the Vedas” (vedānaṁ pāragū). Or they describe them as “accomplished in the Vedas” (vedasampanno). That may be how they described themselves, too.

Nowadays we call this religious tradition “Brahmanism.” Its not called “Hinduism,” which is a much later term.

It’s true that Brahmanism was one of the phenomena that, combined with others, became Hinduism. But it wasn’t Hinduism.

Wikipedia summarizes the current understanding of the relationship of Brahmanism and Hinduism by saying: “Brahmanism was one of the major influences that shaped contemporary Hinduism, when it was synthesized with the non-Vedic Indo-Aryan religious heritage of the eastern Ganges plain (which also gave rise to Buddhism and Jainism), and with local religious traditions.” [Emphasis added]

Another Wikipedia article says, “Hinduism developed as a fusion or synthesis of practices and ideas from the ancient Vedic religion and elements and deities from other local Indian traditions.”

Brahmanism was an influence on Hinduism, which emerged later, but it was just one influence.

The baffled Hindu time-traveler

Let’s imagine you were to take a modern Hindu back to the time of the Buddha. They probably would not accept that they and the Brahmins back then were doing the same thing.

The modern Hindu would see Brahmins reciting the Vedas, and think, “Cool!”

But then they’d see them sacrificing cattle and be shocked.

The modern Hindu would see no temples in the Buddha’s India. He’d hear Brahmins talk of an afterlife in heaven or with the ancestors, but no talk of reincarnation. But he’d hear Buddhists talking about rebirth all the time. He’d also hear Buddhists, but not Brahmins, talking about samsara.

The modern Brahmin would see animist cultures worshipping local deities and believe that this was “Hinduism,” but the Brahmins of the Buddha’s time would not recognize the animists as being part of their own religious tradition and the animists would certain not regard themselves as being part of Brahmanism.

As Bhikkhu Sujato says in a talk on whether the Buddha was a Hindu, “what we understand of as Hinduism today didn’t even remotely exist in the time of the Buddha.”

Buddhism is older than Hinduism

One thing that will surprise many people is that Buddhism is older than Hinduism. The Buddha established the Buddhadharma during his lifetime, some 2,500 years ago. Hinduism is much younger.

When something comes about through a slow process of amalgamation and innovation, it’s hard to say when exactly it started. The formation of what we now call Hinduism took place from about the 5th to the 8th centuries, according to Bhikkhu Sujato, in the same talk I just mentioned. This, he says, was the birth of Hinduism. Guy Welbon, in “Hindu Beginnings” puts the essential synthesis rather earlier. He wrote, “It is only at or just before the beginning of the Common Era that the key tendencies, the crucial elements that would be encompassed in Hindu traditions, collectively came together.” The disagreement arises simply because it’s not possible to pin down precisely the line when a slowly evolving entity stops being one thing and starts being another.

Bhikkhu Sujato points out, “If India has always been a Hindu country, how come for hundreds of years in the archaeological record — nearly a millennium in fact — we find nothing of Hinduism and plenty of things of Buddhism and Jainism?”

Note that this isn’t some trick of language — that “Hinduism” is a new term, while the religion itself dates back to the Buddha. No, the religion itself dates from a period several centuries to a millennium after the Buddha. What came before was a collection of different religious traditions that did not consider themselves to be doing the same thing.

Sakya was not Brahmanical

But even if we were to stretch the definition of Hinduism — way beyond credibility — so that it were to encompass the Brahmanical practices of the Buddha’s time, the Buddha’s people did not even practice mainstream Brahmanical teachings.

I’ve searched the scriptures looking for a single encounter between the Buddha and a Brahmin in his homeland, Sakya, and found nothing. I’ve seen mention of “Brahmin villages” in surrounding territories (these were lands gifted by kings to Brahmin settlers) but none in Sakya.

In fact the single mention I’ve come across of a Brahmin being in Sakya was in a conversation the Buddha had with someone called Ambaṭṭha, who recounted to the Buddha how he had once, at the instruction of his teacher, visited the capital, Kapilavatthu, and had been treated with an utter lack of respect. The Sakyans, he said, giggled at him and wouldn’t even offer him a seat. The Sakyans treated him like an alien curiosity, not as a religious teacher. Ambaṭṭha doesn’t talk about having met any other Brahmins in Sakya.

Sakya was not Brahmin-friendly.

Sakya was opposed to Brahmanical beliefs and practices

The Sakyans had a belief system that was at odds with that of the Brahmins. Brahmins were obsessed with caste, or varṇa, which was a four-fold system of socioreligious purity, with themselves at the top. The Buddha’s people saw themselves as warriors (khattiyas, which literally means “owners”). They saw themselves as superior to the Brahmins.

The Sakyans being khattiyas doesn’t mean that soldiering was necessarily their profession. Sakya didn’t have a standing army. Most men living there would have been farmers, craft workers, or traders, although probably all males had some martial training.

The thing is: the fact that they saw themselves as superior to the Brahmins utterly conflicts with Brahmin belief. To the Brahmins, the fourfold social-religious hierarchy with themselves at the top was ordained by the gods and spelled out in their scriptures. The Sakyans insisting they were superior to the Brahmins was a rejection of the Brahmin world view, and of their religious scriptures.

The Sakyans had completely different beliefs of social classes. To the Brahmins, one’s caste was an intrinsic part of one’s being, and you could no more change your caste than you could change your species. One of the Buddha’s arguments against the Brahmin’s views on social and religious hierarchy was that there were places — Sakya was one of them — where there were only two social classes: masters and servants, and it was possible for a master to become a servant and vice versa. There was nothing intrinsic about one’s social worth, and these class distinctions were just social conventions. To the Sakyans, caste, in the Brahmanical sense, didn’t really exist. This is a huge deal. It’s an utter rejection of a key part of Brahmanical teachings.

The Sakyans’ religion

One of the Buddha’s epithets was Ādiccabandhu, or “Kinsman of the Sun.” Some people have suggested that the Sakyans were therefore sun-worshippers. But there’s no direct evidence they were, and in fact there’s no mention in the Buddhist scriptures of any gods the Sakyans might have worshipped. Whoever or whatever they worshipped, they apparently did it without the help of Brahmin priests.

They did seem to regard certain trees as sacred, and used them as shrines. The oldest known shrine in Sakya was a sacred tree at the Buddha’s birthplace, Lumbini. Trees as special places crop up all the time in the Buddhist scriptures. The Buddha was born under a tree. He realized that he’d previously had a glimpse of the path to enlightenment while he’d been sitting under a tree as a boy. He got enlightened under a tree. He taught under trees, encouraged people to meditate at the foot of trees, and died under a tree.

There are many mentions of yakkhas (native spirits that inhabited trees, mountains, etc.) in the Pāli texts, which may mean that the Sakyans worshiped not the trees themselves, but the spirits they believed resided in them. To my mind it’s highly likely that the Sakyans were animists.

I’ve seen no mention of animal sacrifice of ritual fires in Sakya, or of ritual bathing or other purification rituals, all of which were important parts of Brahmanical practice. Sakyans buried the cremated remains of their dead in burial mounds known as stupas. This was not a Brahmanical practice.

So the Buddha’s tribe (presumably along with other tribes in what is now southern Nepal) seem to have had their own religious tradition, entirely separate from what the Brahmins were doing.

The mystery of the name “Gautama”

The single strongest argument that the Sakyans were part of orthodox Brahmanism is their gotra (clan) name, which was Gautama, or Gotama. This is traditionally a Brahmin name. In fact it’s the name of a Brahmin seer (rishi), from whom the Sakyans claimed descent. This descent wasn’t genetic, incidentally (the rishi was not their ancestor), but cultural and symbolic.

How would non-Brahmins end up with a Brahmin name?

Bhikkhu Sujato explains:

As the brahmins spread across India, one of their chief tasks was to ally with the local kings and provide legitimization for kingship via their rituals and traditions. There were different Brahmanical lineages according to the specifics of how the rituals were performed and the texts transmitted, and these are sometimes raced back to the ancient seers (rishi) who originated the lineage.

Since the Sakyans didn’t embrace anything like Brahainical orthodoxy, we might safely assume that this connection with the rishi Gautama was fairly superficial. It may be that a monarch who the Sakyans were vassals of, forced them to undergo some kind of ritual blessing by a brahmin of the Gautama lineage. This would be similar to the way in which some pagans, under the influence of Christianity, underwent “conversion” but carried on with their old ways regardless.

The Sakyans were not alone in being identified with an ancient seer. The neighboring Mallas were called Vāseṭṭhas, after another ancient rishi, the sage Vāseṭṭha (Skt. Vasiṣṭha). They, too, were khattiyas (warriors), rather than Brahmins.

So the Buddha was not a Hindu.

First, Hinduism didn’t exist.

Second, the Sakyan people did not follow or even agree with Brahmanical practices.

Myths as propaganda

To say that the Buddha had been a “Hindu prince” is horribly inaccurate. It also feeds into Hindus’ claims that theirs is “India’s oldest religion” — which is simply propaganda.

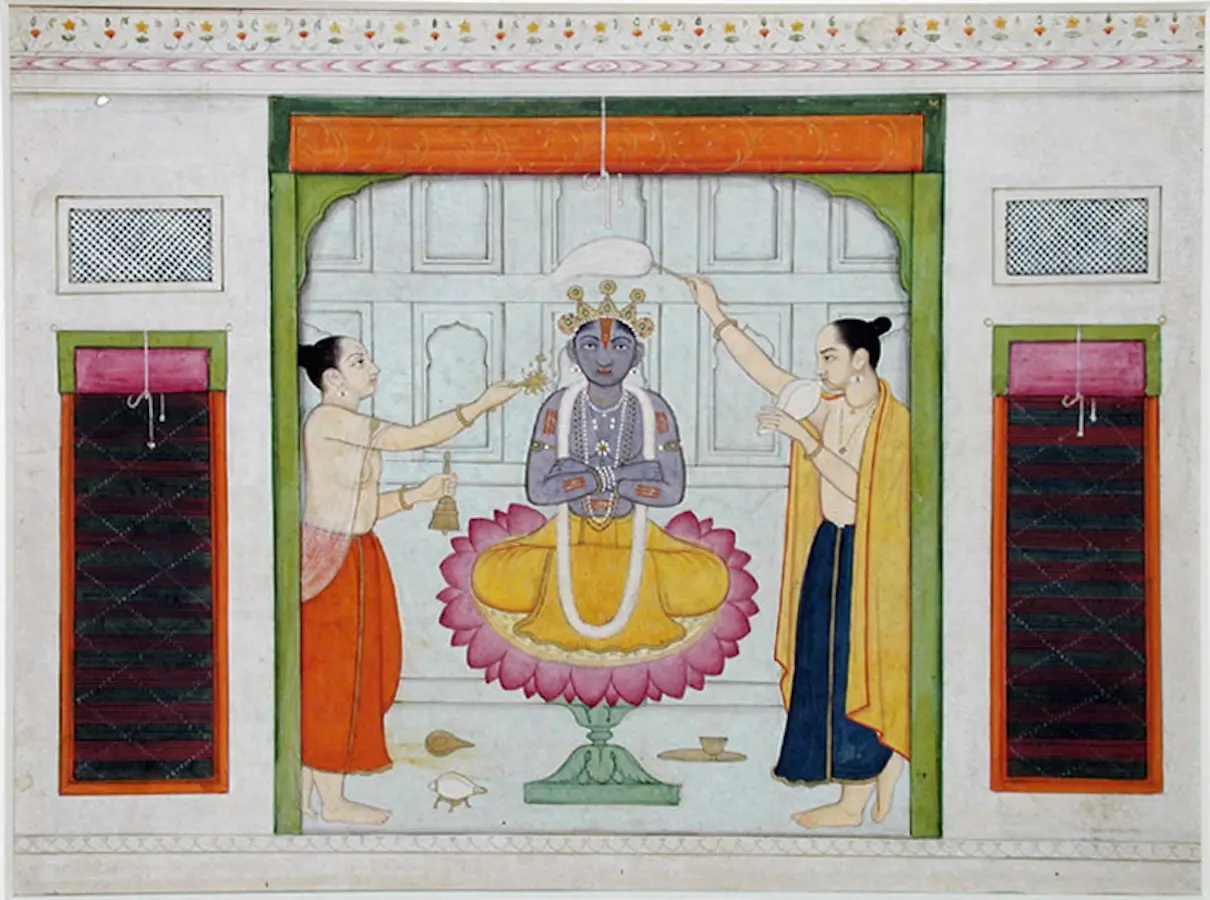

Hindus claim that the Buddha was really a Hindu, and even that he was an incarnation of Vishnu (seen in the illustration above) . The most common reason given is that the Buddha/Vishnu came to argue against animal sacrifice (which has a very ancient history in the Vedas.)

Hindus often talk about their religion being very tolerant. But that tolerance can take the form of saying “No matter what you think, we consider you part of our religion. And because you’re part of our religion, we’re in charge of you.” For example, for a long time, Hindus have claimed ownership over the Buddhist holy site of Bodh Gaya. After all, Buddhism was “part of Hinduism.” Recently, Buddhist monks have been on hunger strike to protest the Indian law that gives control of a Buddhist site to Hindus.

A court case forced Hindus to give Buddhists a minority say in the running of Bodh Gaya, but still gave Hindus ultimate control over the site. Just to be clear, it is one hundred percent a Buddhist site with no historical connection with Hinduism or its predecessor religions. And it’s controlled by Hindus.

The myth of the Buddha having been born a Hindu feeds the myth of him having been a “Hindu reformer.” And this provides fuel for Hindus who want to appropriate Buddhist holy places.

Hinduism and fascism

Hinduism’s tendency to “tolerantly” absorb and exert dominance over Buddhism and other religious traditions has evolved into what’s called the “Hindutva” movement, which is a blend of Hinduism with ideas borrowed from European fascism. Hindutva is a “political ideology encompassing the cultural justification of Hindu nationalism and the belief in establishing Hindu hegemony within India,” according to Wikipedia.

Claims that the Buddha was born a Hindu are propaganda, feeding that unhealthy political trend. Such claims are not just inaccurate, but are politically harmful in a way that is damaging to Buddhism itself.