It’s my birthday today, and it’s unlike any I can remember from my now 63 years on this planet.

It’s the first birthday I’ve had since my mother* passed away on Christmas Eve, just 11 days ago.

My younger sister died just over a year ago, and I wrote then about how my practice helped me with the grief I felt. I’m not going to write about grief today, mainly because my primary emotions have been of relief and gratitude that she didn’t suffer longer. Her last days were pretty grim as she struggled to breathe, and things were only going to get worse. Today I want to look in a different direction.

Also see:

On previous birthdays my focus has usually been on myself: I am a year older. I have completed another cycle around the sun. Happy Birthday to me!

Now I’m more aware of the “birth” part of birthday. Today is the anniversary of the day that my mother gave birth to me. So today seems more about her than it is about me.

She carried me inside her body for more than nine months (I was fashionably late). I grew from a single cell into a baby nourished entirely by her; her body became my body.

Today I very much have a sense that I am a part of her that has, in a way, budded off and continues her existence in the world, even though she is no longer here. My life is a continuation of her life.

As I wrote in my book, Living as a River, parts of our mother often live on within us.

During gestation…

[C]ells from your mother’s body can cross the placental barrier and infiltrate your own body, in a process called “microchimerism.” These maternal cells can settle down anywhere in the body, including the blood, heart, liver, and thymus gland … These cellular interlopers have been shown to live within the offspring’s body for decades, and they may be with us for life. You are not just you, you’re your mother too.

These cells have been found in the pancreases of diabetic individuals, pumping out the insulin that the person can’t manufacture themselves. They’ve been found in damaged heart tissue, and are thought to be trying to repair it.

My mother may still be within me, trying to keep me healthy. (Admittedly, though, some autoimmune disease is believed to be a reaction to the presence of certain material cells.)

My brain and mind were profoundly shaped by her. My first experience of love was her love. We know from the horrible experiments done by Harry Harlow on baby rhesus monkeys how maternal deprivation destroys children. As one description of Harlow’s work says,

[T]he monkeys showed disturbed behavior, staring blankly, circling their cages, and engaging in self-mutilation. When the isolated infants were re-introduced to the group, they were unsure of how to interact — many stayed separate from the group, and some even died after refusing to eat.

Harlow’s experiment also proves the converse: the gift of love creates our humanity. Not our biological, chromosomal humanity, but our sense of ourselves as thinking, feeling beings connected in love with other thinking, feeling beings.

This was one of my mother’s gifts to me.

A child initially learns most of its language from its mother. The fact that I’m using language to communicate with you now is me passing that particular gift from her.

There are many character traits I picked up from her as well, not through conscious imitation but through unconscious imprinting. Some of those traits are helpful and some less so, but the point is that here too my life is a continuation of her life.

She inherited character traits from her parents, and they from theirs. As with the presence of maternal cells in our bodies, this is by no means all positive. Perhaps my task in life is to take the best of what has been passed on to me and amplify it, and to take the worst and eradicate it. And thus I can pass on the best of my mother to the world — not just through my children, but through all my contacts with other human beings.

My mother died on Christmas Eve. So I’ve now gone through one Christmas, New Year, and birthday without her. There’s a certain amount of grief been present, and there may be more to come — perhaps especially when those celebrations come around again — but that will fade. The love and gratitude, however, will remain.

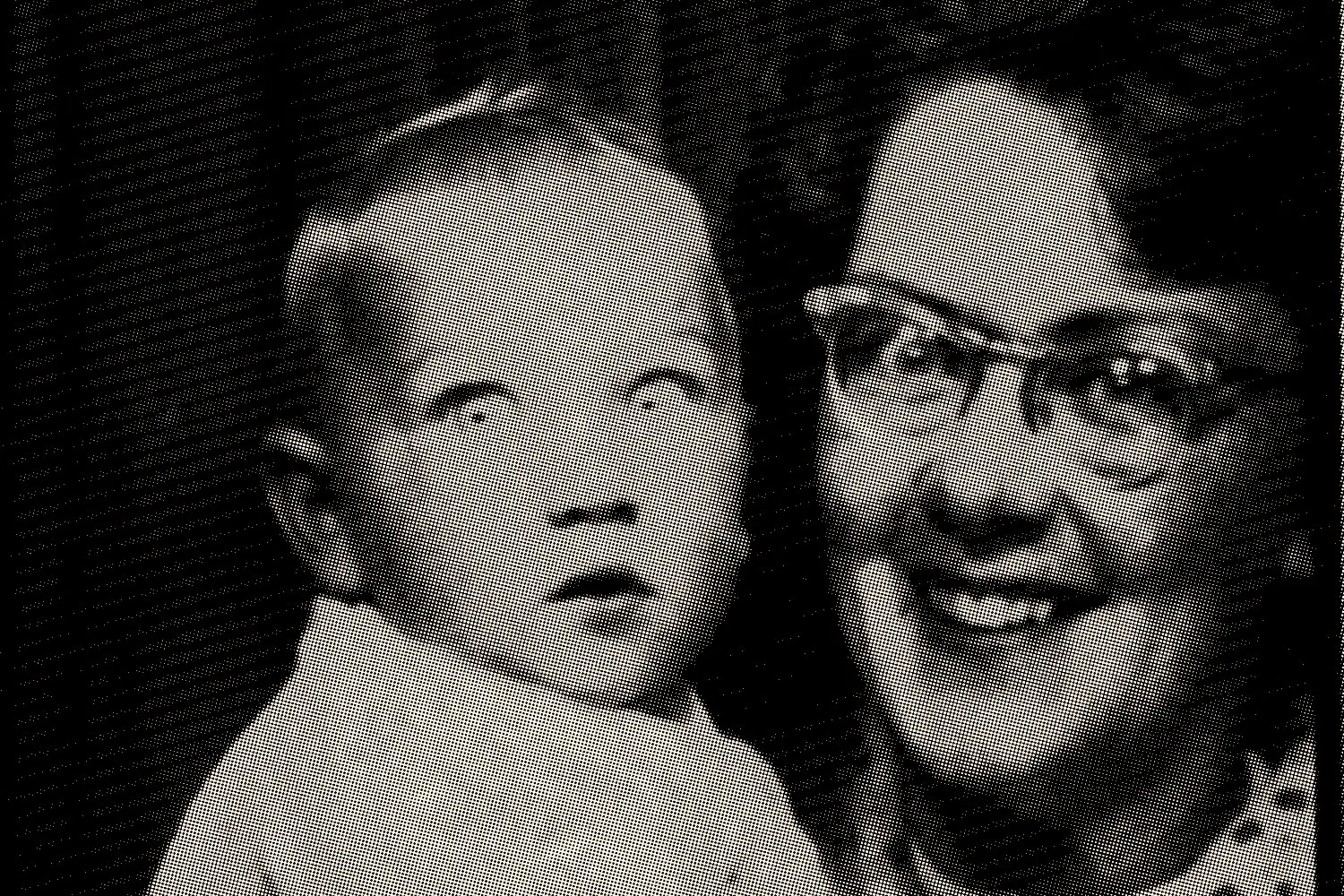

*Her name was Eleanor Dorothy Stephen. She was born 16th March, 1938. Her birth certificate lists her family name as Tragheim, but she always went by Tragham, my grandad having begun to adopt a less German-sounding last name during the war.